It’s an old joke among modelers that instructions are merely suggestions. While of course generally offered in jest, I think to a certain extent there is a grain of truth to that in the way we may approach a project. In my own experience, the beginning of a new build would often mean a general perusal of the instructions, a look at the parts, and then I’d dive right in.

Yet more often than I’d like to admit, that process would come back to haunt me. Many times I’d find assemblies constructed that would later prove difficult to access for painting. Or that I’d not properly checked the fit of parts to be added later – discovering too late that an incorrect placement caused fit issues.

And most manufacturers don’t present instruction sequences in a way that is cognizant of the realities of filling seams, painting, and other detail work. It’s not that they are unfriendly towards the modelers work, but rather that the build process is seen as much as an engineering issue as anything. The planning is left up to the modeler.

After far too many gaffes, I finally decided to take control of things and spend more time in deliberate planning.

The process may take a bit longer, but I’d submit is produces better results, and makes for a smoother build experience.

Highlight Those Suggestions

The first step in my builds now is to start with a very, very thorough look at the instructions. I’ll have the sprues standing by, and as I look over each step in the assembly sequence, a check will be made on the sprue to identify the part. Quite often I’ll snip parts off the sprue, and actually test fit the parts together. In a few cases, I’ll even “build” whole sections using tape and poster tack.

As I go through this exercise, I’ll make notes on the instructions, reminding myself to paint some sections ahead of time, or to wait for painting until later. If a decal is needed, I’ll use a highlight marker to notate that, and make sure I don’t miss it.

An example of a very important way that this can be helpful is a reminder to add nose weight to aircraft that may suffer from “tail sit” otherwise. I often get so excited (or hurried) in a build that in a race to get to the fun part – painting and weathering – I’ll leave out this fundamental step. This has often necessitated going to great lengths later to add nose weight in after the fact, a process that is often quite complicated and laborious.

Yet the solution when doing proper planning is simple – add a warning to the instructions in BOLD LETTERS that say something to the effect of “yo Skippy, add the weights.” I’ve even gone so far as to adding a piece of tape inside the fuselage with a warning on it, so I can’t miss it.

Think About The Final Result

Another way that I use this instruction and parts perusal for purposeful planning is to “visualize” how the build will come together. In a sense, I mentally build the model in my mind, thinking of what will need to be primed, painted, decaled, varnished, weathered, glued, and whatever is will be done to get to the end. In fact, on some models that I am particularly excited about building, this “brain build” process can wake me up at night, with thoughts of how to best order the steps.

This planning has been extremely beneficial in helping me anticipate when things will need to be painted, where glue will go, and how things will work in the weathering process. And when it comes to Bandai kits, with their finicky plastic which can literally fall apart when bare styrene is exposed to some thinners, thinking in terms of how later weathering will impact the assembly is critical.

Again – I rely on the notes process in the instructions as prompts to make sure I have thoroughly thought through these things. It’s only with all of that in place and a set of edited instructions that I begin to dive into the build.

A Note About The Model

When the upper and lower half of the model is joined together, there is a very prominent ridge sticking out on the lower hull. It runs from just aft of the cockpit to the nose, getting wider towards the front.

When I first noted this, I thought the unthinkable had occurred – Bandai had messed up!

I sent a note to my friend Ant Crumb, of Bashing Kits fame. Ant has done some incredible builds of Bandai’s Star Wars kits, and I knew he’d recently built this one.

As it turns out, this detail is faithful to the original – a feature I’d never actually noted.

So… panic mode was turned off. Thanks for the calm assurances Ant!

A Practical Example

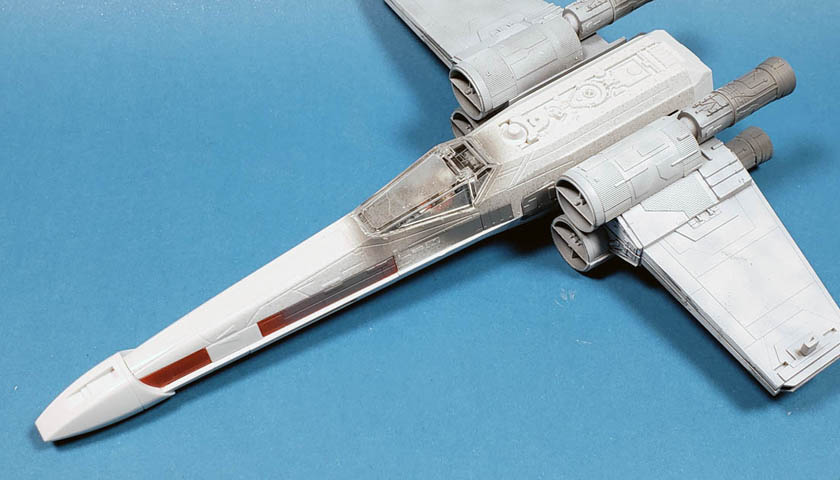

A simple example of how this process works can be demonstrated with Bandai’s 1/72 X-Wing Fighter, a kit I have recently started working on. The kit is typical Bandai – gorgeous parts casting, amazing fit, cool gimmicks… and a very non-traditional parts breakdown.

Because many Bandai kits are designed to be assembled without painting, they often have multi-colored parts. This of course requires engineering that will separate various panels out from one another, resulting in an almost “Lego” style build. And while the fit is very precise and tight, it can cause a very different approach to finishing and painting.

Additionally, this model’s “gimmick” is an opening and closing wing, to replicate the way they worked in the movie. Of course, this also will impact the engineering, and the realities of the build, in order to make this work.

As I looked over the instructions and the parts, a non-standard plan began to emerge in my brain. (Which is a scary place to be anyway… 🙂 ) While the cockpit “tub” could be painted and weathered in the way I typically do it, the assembly of the fuselage and wings required a different approach.

Instead of just being a simple “stick upper and lower fuselage together then add wings”, each of the fuselage sections requires multiple parts to be added on, forming all of the panels along the sides. And the wings are split in a very odd (but logical) way to facilitate the opening and closing. While there are two full span wing parts, each consists of the lower section from one side being paired with the upper section from the other. A pivot pin on one set mates to a hole in the other, and this allows the wings to open up into the familiar “X” shape.

Of course, this results in the inside sections of both upper and lower wings not being fully accessible after assembly, so painting is required ahead of time in order to make sure the details are all accounted for.

I started by first painting, highlighting, and applying a wash to the cockpit and instrument console. While these parts have nice cast in detail, I decided to go with the kit supplied waterslide decals. As the finished model will have the canopy sealed closed, I thought the decals would show better if viewed through clear canopy.

The decals are of good quality, though I wish there were a bit less carrier film around them. (Cartograph has spoiled me!) And the shapes were a slight bit odd to get in place. I realized afterwards I should have cut the instrument panel decals along the lines of the various faces they needed to fit to. Still, with a coat of Solvaset, all snuggled down nicely and will look the part once viewed in situ.

The pilot was painted with various Vallejo paints, given a simple acrylic wash, and some very tiny decals were placed on the helmet. While the photos up close look a bit hammered, when viewed from even a foot away, the little fellow looks the part. (At least that’s my story… and I’m sticking to it! 😉 )

With that sorted out, I moved on to painting the inside of the wing faces.

Each section has some recessed detail, and there is a sort of engine section that is at the very root of each section. Leaving these to be painted until the end would of course be very difficult. So all of these factors combined to finalize my build plan.

Here’s a general outline of how I have worked this build to get it to the pre-primer phase:

- Build and paint the cockpit, pilot, and associated parts

- Assemble the upper fuselage half as far as possible

- Assemble each wing section, leaving the laser cannon assemblies off

- Prime the wing assemblies

- Fully paint the inside faces of the wings, including the painting and washing the engine recesses

- Assemble the wing halves, and then join them to the fuselage halves, adding the final fuselage panels as per the instruction sequence.

I’d considered fully painting all the parts prior to assembly, as I’d done with the A-Wing fighter. However, this model has so many colored panels that are split across sections, I didn’t feel it would work well to take this approach. And while Bandai does provide decals for all of the panels, I had concerns that they may not work nicely with all of the surface detail. So my plan is to go through the somewhat laborious process of masking it all off, and painting it with my airbrush.

The final result thus far is the familiar shape of the classic X-Wing Fighter. I wanted to show it “pre-primer” so that it could better convey the sense of how taking a more structured approach to building goes through many stages.

And as a bit of a footnote, despite all the planning, I realized I did miss painting a colored bit on the inside panel of one wing… so a decal will need to be used there. What’s the old saying? The best laid plans of mice and men…

While each build will certainly dictate different approaches, I hope this general discussion and then specific insight has given you ideas that will be helpful, and that you can then extend and build upon. I can’t say I’m doing anything unique, but it did prove to be quite helpful to me as I progress down this plastic highway.

And most importantly – have fun with it!

Leave a Reply